WITH ELEANOR HARWOOD GALLERY

BEHIND THE SCENES WITH ELEANOR HARWOOD GALLERY

Eleanor Harwood discusses her journey from an art-curious student to becoming a prominent San Francisco gallery owner, highlighting how her experience curating at Adobe Books Backroom Gallery in the early 2000s helped shape her path in the art world. She shares insights about the evolution of the Bay Area art scene, her approach to selecting artists, and her vision for fostering community through her gallery's programming.

Paul Wackers, "Stepping into the Sun", acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 48 x 54 in. Image courtesy Eleanor Harwood Gallery.

CL: How did your interest in art come about?

EH: I've always been interested in art since I was a little kid. I received painting and drawing awards during school. However, I didn't like my art teacher in high school, so I stopped thinking about it much after that.

In undergrad, I studied American Studies with an emphasis in visual studies, focusing on 20th century and 19th century American painting, art, and architecture.I also did film and video production as a double major, so everything was visual in some way. At that time, I had no idea what I wanted to do as a career.

I was doing video artwork in undergrad, and during my thesis presentation, my thesis panel asked me where I would show the work I was making and talking about, which was confessional video work. I had no idea what the answer was – I didn't know about art galleries or museum galleries at 20, no idea that those were the venues for showing experimental work. The funny part is that I'm still in touch with those professors from that thesis meeting: Larry Andrews, who's married to one of the artists who shows upstairs at one of the Minnesota Street Project galleries, and Chip Lord from Ant Farm, who shows with Rena Bransten gallery. It's hilarious to me that I keep seeing these people now, and that the answer to their question was commercial galleries. Finding the commercial side of the art world was a very winding path.

CL: What drew you to film and video?

EH: It seemed creative and I had friends who were in the film department. I was doing film and video, but not in a very narrative way. I was more interested in experimental video art and documentaries. For my film thesis project, I hand-painted a 16-millimeter film – thousands of frames painted with colored ink.

Once I graduated I interned at Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC). I worked in the documentary film and experimental video world and for a while until I got headhunted by a special effects company during the first dot-com boom here.

CL: And did you grow up here as well?

EH: I grew up overseas and then moved to America when I was 13. I lived in Los Gatos and went to UC Santa Cruz for undergrad. Then I moved to San Francisco for my internship and have been here since.

While working in video editing and web production I also went to grad school at CCA for a Master's degree in painting. During that time, I was also curating Adobe Books Backroom Gallery. It was an incredible space – a sort of incubator and crucible for the Mission School artists. It is a bookstore on 16th Street and Valencia, owned by Andrew McKinley. He was, and still is, one of those people who allowed pretty much anything to happen in a space. You'd find all sorts of people there – adults with various disabilities who felt comfortable hanging out, artists, musicians, and misfits. Andrew always hired artists or writers to work there. It was like a salon setting, similar to what you'd read about in Paris with Gertrude Stein.

Amanda Eicher started the gallery, but when she wanted to focus on her own art practice, I took over. I ran it from late 2001 to 2006 before opening my own space. Though it wasn't paid, many big names showed there – Chris Johanson had one of his first shows there, along with Chris Corrales, Joe Jackson, Simon Evans, and Sean O'Dell. They were all Mission School artists, and Jack Hanley picked up many of them. The space became the nexus of the Mission School movement.

I got involved as much for the art as for the culture and community. I finally felt like I had found a community I liked. That it professionalized and turned into a career was very accidental. I went to my first art fair after being invited by people who had seen my curating at Adobe Books. When I saw that you could do this as a job, I was amazed. I went by myself, put it all up, worked the fair, and decided this was what I wanted to do. I opened my own space in 2006. I'm sure there are people who work at galleries whose aim is to be a gallery owner, but I never worked at a gallery. It was all made up as I went along.

Kira Dominguez Hultgren “Our Daily Parenthetical”. Photography Shaun Roberts.

CL: Most people don't understand how the art world works. Even with museum exhibitions – I just learned a couple of years ago that they need donors to put on exhibitions of someone's artwork. I had thought museums just had the money to do it. It's so interesting that they have to get patrons involved.

EH: Yes, I think the mechanics of the whole industry are completely invisible. For example, designers and art consultants make up a huge portion of gallery sales. I'm delighted by this now because you meet people and reach customers that you would never otherwise connect with. When I first started, I was really prickly and weird about it because I didn't understand. I thought clients should just come directly to the gallery, but that's not how it works at all. It's a whole ecosystem where everyone works together.

CL: It's also about repeat clients, right? Where maybe one person will come back once in a while, whereas designers have lots of clients who need art.

EH: Yes, and those relationships have become the most valuable and interesting part of my job over these nearly 20 years. I've been working with some people for years and years now. I understand that the percentage designers make from the sale is how they stay in business. It can be difficult because new artists who work with the gallery are sometimes very uncomfortable with sharing percentages. They don't really understand how it all works and how necessary it is for the longevity of everyone's careers.

There's a reason to give away a percentage – it actually benefits the artist. If you can get your work into editorial shots and have your name credited, that's valuable marketing. Sometimes it can feel uncomfortable, but I think most people have come to understand the value of marketing and having a broader reach via professionals posting their designs and tagging the artists.

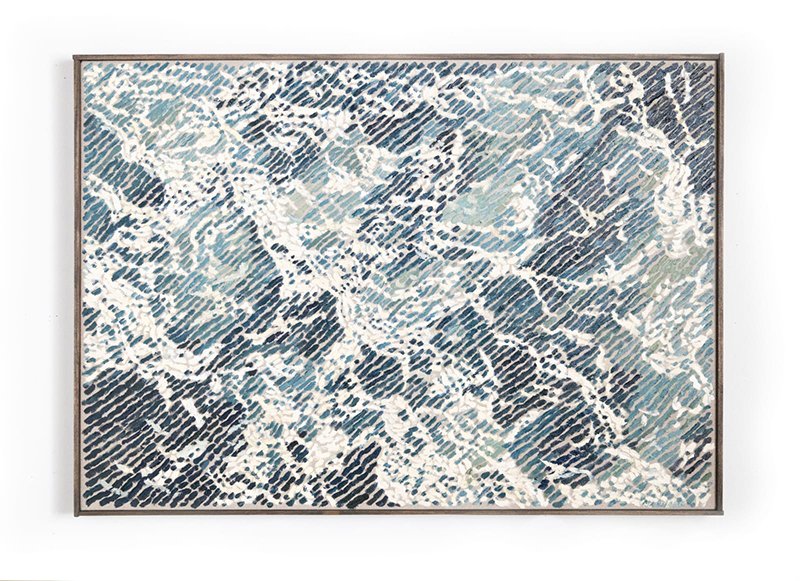

Martin Machado, My Wake Series on Linen 11, 2023. Oil on linen, 28 x 41 in. Courtesy Eleanor Harwood Gallery.

CL: Since starting your gallery in 2006, how have you seen the industry evolve, or how have you evolved the gallery and your approach to art?

EH: I think I've always just shown what I liked. I haven't responded too much to market pressures or what people want to see. I don't think I realized what I was specializing in until the last few years – my focus is really on Bay Area artists, the best people from this area, and developing those careers. Frequently they move away and they're not from here anymore but we still work with them. I like to show artists that have part of their history attached to the Bay Area.I think it's because I'm interested in the community in general, and by hosting shows that feel generous and generative for our continuing community, I feel we keep growing and supporting it. Our new project space, the smaller secondary gallery, has allowed me to have group shows in the back, and have artists who are showing a solo show in the main space curate a group show that opens alongside their exhibit. It’s been really refreshing to see work by new artists and also to present works that are much more affordable.

CL: You're fostering that community. What I thought was interesting was when you talked about Adobe Books, where you finally found your community. How has that changed over time with the tech boom?

EH: Those are good questions. It's changed a lot because it used to be way cheaper to survive in the Bay Area and have a studio here. What I've seen shift tremendously in San Francisco over 25 years of curating and being in that community is that people used to be able to be scrappy – maybe work at a cafe and manage living in a house and having a studio. Some of them lived in closets, but they made it work. So there were more people doing art at that level who didn't necessarily have MFA’s.

I've seen a lot of professionalization happen during that period where a lot more people have gone through MFA programs. I think MFA’s are incredible for the focus and time they give people, but I think they're problematic for the debt they create. It becomes this catch-22 where artists have to figure out how to pay off their student loans and living cheaply in the Bay Area while managing that debt is much more difficult than it used to be.

It used to be that people would come in and be delighted to show and be totally happy if a painting sold for $200. But when you have all that pressure and that concept of professionalization, people think their first painting in their first show should be $5,000, not based on their CV record, or market demand. Their concept of value has radically shifted. I don't really want to price things that way. I want to price them based on CV, reputation, and demand, and sort of slowly raise prices as an artist gains recognition.

Mary Finlayson, "Flowers with Books and Quilts", 2023. Mosaic tile on panel, 48 x 40 in. Courtesy Eleanor Harwood Gallery.

CL: How do you handle that for your own gallery when you're talking to new artists? Do you end up convincing them about what's reasonable?

EH: Generally speaking, yes, I think it is shifting back a little bit as the art market has cooled from its speculative heyday, which is good. That peak was about four years ago, as well as the height of real estate costs. I don't run across that many 25-year-olds who want to price a painting at $10,000 for their first show anymore. But you can go to other galleries and they tell you it's an "emerging artist price" at $25,000. So, you know, it can be a lot of smoke and mirrors.

In our back room gallery, we'll have photo shows where pieces are $150. I've really enjoyed doing that – it's sort of brought me back to my Adobe Books roots. When the main gallery has a show, I've generally been asking the artist who's exhibiting to curate the back room. They're pulling from all these people who are not known and who maybe don't even think of themselves primarily as artists. That's been really great because it's affordable, so people can come in and just buy something because they like it, without the consideration of whether it's an appropriate investment. When you hit certain price points, those are the questions that come up. I do fundamentally believe you should just buy what you love. That's it. No one can predict a career. In my twenties, I used to believe a little bit more in the stratospheric value that people would gain and attain. But now I think you should just buy what you like. If the value increases, fantastic.

CL: How do you find the artists that you like? What's your approach to curating the exhibits?

EH: I look at everything. Artists often ask if people will review work, and a lot of galleries say they're not open to submissions. But I literally look at every single email I get. I have stock responses to keep it quick because most of the work won’t resonate or be a fit with my gallery or taste for whatever reason. However, remaining open is how I’ve found some of our most recent additions to the gallery roster. Martin Machado is a really good example – he just walked in and said, "Hey, can I show you my paintings?" I was in the right mood that day, maybe I didn't have crazy deadlines, and I was like, "Okay." When I looked, I thought they were amazing, so I arranged a studio visit.

I also have very personal criteria such as: is the person nice? Do they seem like they're going to be easy to work with, low drama? Also, will they meet their deadlines and have a really good studio practice? Those are really just ways to try to assess discipline. The older I've gotten, the more I realize that anybody who's good at anything just really works hard at it. That's almost all it is. There's talent of course, but mostly it's just showing up and doing the thing a lot is how we get good at anything. My criteria has gotten a little less romantic than it used to be.

CL: No more tortured artists in the back room?

EH: Not interested. Well, maybe a little bit tortured. Depends how good the work is.

CL: You have a focus on Bay Area artists. Have you found any themes besides that in terms of what draws you to a particular artist?

EH: Definitely. I think part of what dovetails with what I was saying about practice and professionalism is that I'm drawn to people who have really high levels of craft. For example that means being really excellent at your painting execution and mixing techniques. For example, Martin Machado is an excellent oil painter. He knows how to do his ground color, build up under painting, and create the effect he wants because he is so deft with his technique.

Hunter Saxony III does calligraphy that comes from practicing various mark-making traditions. He spends hours looking at historical examples of different calligraphy types from various eras and cultures. His ability to create beautiful line work and smooth gestures comes from years of practice developing control. Kira Dominguez Hultgren creates huge textile installations. Her work is conceptual on a content level but the execution involves exceptional weaving technique and being well-educated about different cultural approaches to weaving – whether it's using brooms and twigs or working with a jacquard loom where she's programming it technologically. I'm really drawn to people who go deep in their practice and thoroughly research things. That's the thread – they're just really good at whatever it is they're doing. So it's not like I'm specifically a painting gallery or textile gallery.

Mary Finlayson Installation image “Inside, Inside”. Photography Shaun Roberts.

CL: I first found your gallery and was drawn to it because you represent Paul Wackers. I'm a big fan of his work. How did you connect with him? Was he in the Bay Area?

EH: I first saw his work in person in 2004 or 2005 at a vinyl store on 14th Street. There was something in his works that was kind of moody and interesting and intricate in his painting style, even though they were heavy metal-influenced, like weird shelters in some kind of burned-out world. His paint technique was really great – he's just such a good painter technically. He's figured out how to make abstract expressionist paintings within a completely representative still life. He knows how to mask off areas and be really loose and improvisational, make big smudges of paint, and work in layers and chunks. He knows how to contain it and figure out constraints within that structure. I'm really drawn to that – he makes it look easy, but it's a lot of work.

CL: And he seems to use different techniques that he layers on that are a little unexpected. There's a juxtaposition in the paint techniques.

EH: Yes, it might be spray paint along with something that's rendered carefully, or something splashy and messy, or literal drips. I love that he's not bound by what he's supposed to make or how he's supposed to paint. He just keeps experimenting, which feels loose and joyful in his studio practice.

Kira Dominguez Hultgren, "The Smoke Only Blows in One Direction", 2025.Linen, amoco polyester and other polyesters, cotton, wool, silk, mohair, 63 x 91 x 9 in. Courtesy Eleanor Harwood Gallery.

CL: What is your hope for the art world in the upcoming years? What are your dreams or aspirations for your gallery or the art scene in general?

EH: That's such a big question. Although people keep complaining on Instagram about how the waitlists are over and it's all crashing and burning, I actually like that it's cooling off. I prefer it to be more egalitarian. I like when things kind of reach center – I don't want it too far on either end, no extremes.

For me personally, what I'm looking forward to is continuing to develop the programming for the small space. When we initially built out this space, I thought it was just going to be a viewing room. The first artist who wanted to curate a group show really started us down the path of using that space intentionally. The openings are different now, which is really great. It's bringing in so many people I don't know, which helps us avoid being insular or stuck in our own echo chamber.

When you have a stable of artists and need to have a show every two or three years, it can end up being fairly repetitive. Group shows in the main space don't tend to do well enough, but this smaller space has turned into a really great way to do that. It's low risk, and more often than not, it's selling more than I expect because the prices are lower. The next show in the back will feature Janet Jacobs, who's a more established artist than we have shown in the back previously. She makes very abstract landscape paintings. It's wonderful to have the latitude to present these absolutely beautiful, well-considered, and beautifully executed works alongside Kira Dominguez Hultgrens’ textile show.